Diuretics are a diverse group of medications designed to target the nephron to significantly impact urination. Often referred to casually as “water pills,” these pharmacological agents are the cornerstone of managing conditions ranging from hypertension to heart failure.

While the term suggests a simple function—making you pee—the mechanism is a sophisticated biological bio-hack. These drugs effectively convince the kidneys to release excess fluids and salts (electrolytes) that are accumulating in the body’s tissues, reducing blood volume and easing the workload on the heart.

How Urination Works: The Physiology of Flow

To understand how these drugs work, we first have to understand the natural process they interrupt. Urination is not merely a passive plumbing issue; it is the final result of a complex filtration and balancing act performed by your kidneys. The kidneys process about 180 liters of blood-derived fluid every day, yet we only excrete about 1.5 liters as urine. Where does the rest go? It gets reabsorbed back into the bloodstream.

The golden rule of renal physiology is simple: Water follows salt (sodium).

Under normal conditions, the kidneys filter blood to remove waste, but they aggressively reclaim sodium and water because the body wants to maintain blood pressure and hydration. If the kidneys reabsorb sodium, water flows right back into the blood vessels with it. If the kidneys leave sodium in the tubules, water stays there too, eventually ending up in the bladder. This delicate dance of filtration, reabsorption, and secretion dictates urine volume.

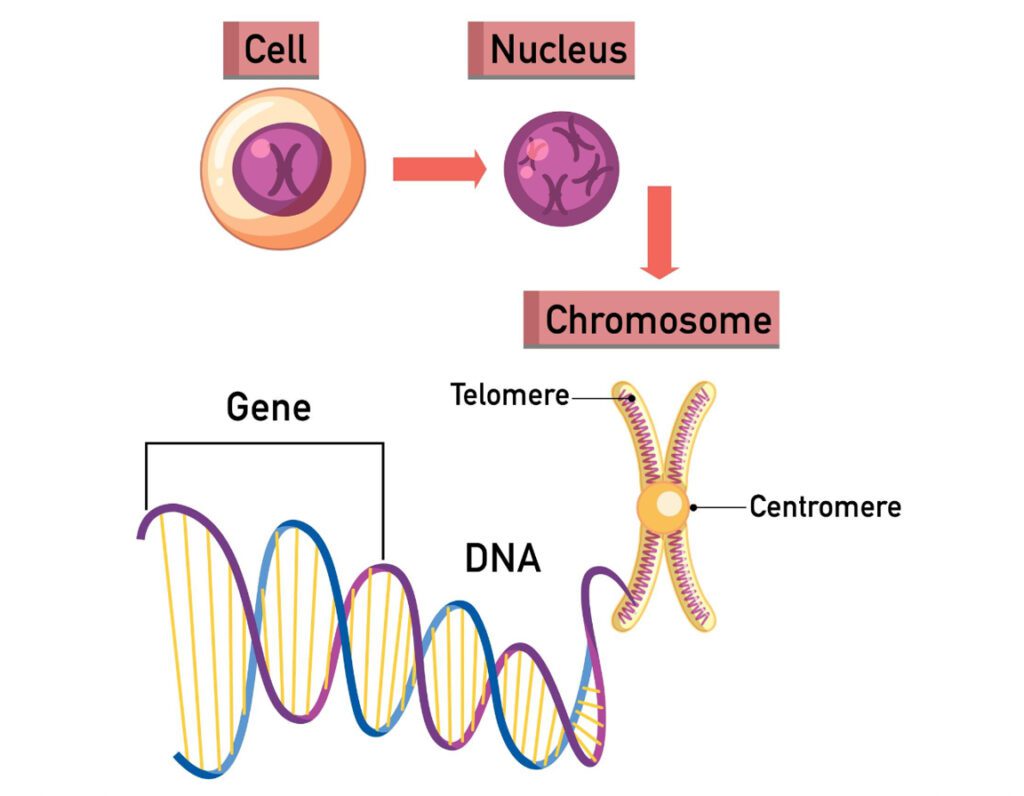

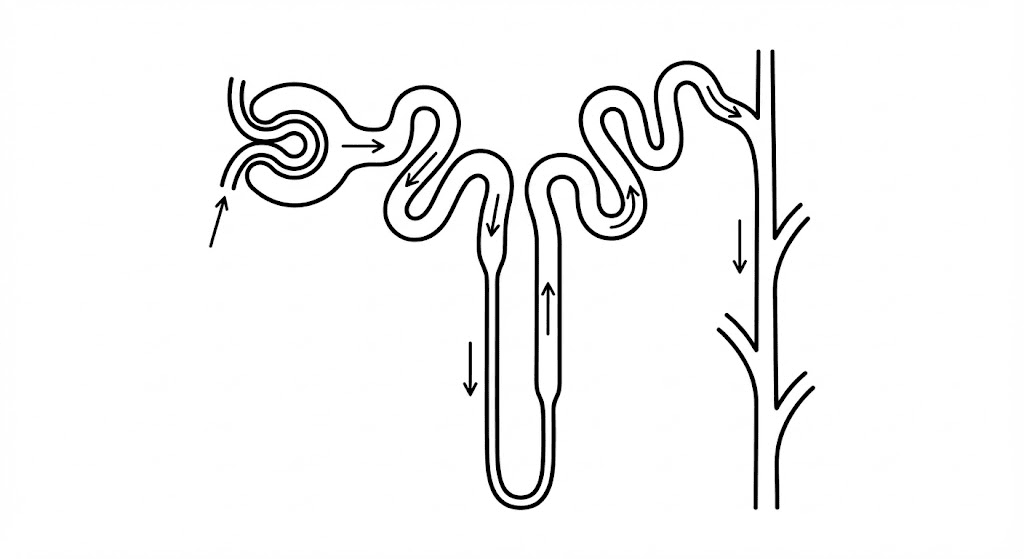

What is a Nephron?

The nephron is the functional unit of the kidney—the microscopic machinery where the magic happens. Each kidney contains approximately one million nephrons. Structurally, the nephron is a long, twisting tube surrounded by blood vessels. It is divided into distinct segments, each with a specialized job in handling electrolytes and water:

- The Glomerulus: The sieve where blood is initially filtered.

- The Proximal Convoluted Tubule (PCT): Where most reabsorption happens (sugar, sodium, bicarbonate).

- The Loop of Henle: A U-shaped loop responsible for concentrating urine.

- The Distal Convoluted Tubule (DCT): Fine-tuning of sodium and calcium.

- The Collecting Duct: The final processing plant where final water adjustments are made before urine exits.

For more detailed anatomical diagrams and physiological breakdowns, you can visit the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

How Do Different Diuretics Affect the Nephron?

So, how do furosemide, bumetanide, torsemide, hydrochlorothiazide, chlorthalidone, spironolactone, triamterene, amiloride, mannitol, acetazolamide, canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, and empagliflozin affect the nephron? The answer lies in “location, location, location.”

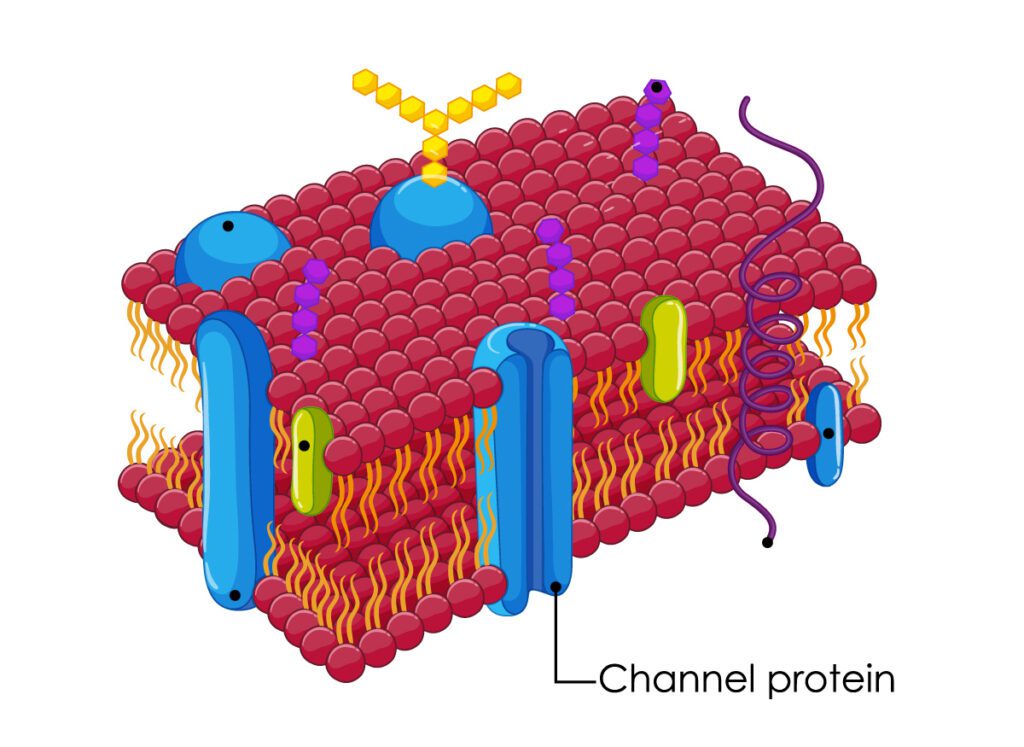

These drugs act as specific inhibitors at different segments of the nephron. They essentially sabotage the kidney’s ability to reabsorb sodium (or glucose, in the case of SGLT2 inhibitors). By blocking the transporter proteins that usually drag salt back into the blood, these drugs force the salt to stay in the urine. Because water follows salt, the water also stays in the urine, leading to increased volume output (diuresis). The specific clinical effect, potency, and side effects depend entirely on which part of the nephron the drug targets.

Acetazolamide: The Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitor

Acetazolamide acts at the very beginning of the nephron, in the Proximal Convoluted Tubule (PCT). It works by inhibiting an enzyme called carbonic anhydrase. This enzyme is crucial for reabsorbing bicarbonate (HCO3-). When acetazolamide blocks this enzyme, the body dumps bicarbonate and sodium into the urine.

Because it acts so early in the nephron, the distal segments often compensate for the sodium loss, making acetazolamide a fairly weak diuretic for fluid removal. However, it is unique because it causes the urine to become alkaline. This makes it incredibly useful for treating metabolic alkalosis or altitude sickness, rather than just simple fluid overload.

Mannitol: The Osmotic Diuretic

Mannitol operates differently than most other diuretics. It doesn’t target a specific receptor or transport pump. Instead, Mannitol is a sugar alcohol that gets filtered into the nephron but cannot be reabsorbed. It acts almost like a magnet for water. It sits in the Proximal Tubule and the Loop of Henle and exerts high osmotic pressure, holding water in the tubule so it can’t escape back into the blood.

Mannitol is rarely used for high blood pressure. Its primary role is in emergency settings, such as reducing intracranial pressure after head trauma or lowering intraocular pressure in acute glaucoma. It forces fluid out of tissues and into the bloodstream to be excreted by the kidneys.

Furosemide: The Loop Diuretic Standard

Moving to the Loop of Henle, specifically the thick ascending limb, we meet the heavy hitters: the Loop Diuretics. Furosemide is the most commonly prescribed drug in this class. It works by blocking the Na+/K+/2Cl- co-transporter. This transporter is responsible for reabsorbing about 25% of the filtered sodium load.

By shutting this door, furosemide unleashes a massive flood of sodium and water. It is incredibly potent—often termed a “high-ceiling” diuretic because increasing the dose continues to increase the diuretic effect. It is the go-to drug for acute pulmonary edema and heart failure.

Bumetanide: Potency in a Small Package

Bumetanide is chemically related to furosemide and works on the exact same transporter in the Loop of Henle. However, bumetanide is significantly more potent on a milligram-for-milligram basis (roughly 40 times more potent than furosemide). It is often utilized when patients are not responding well to furosemide or have severe swelling (edema) that requires a more aggressive approach. Despite the potency difference, the mechanism remains the inhibition of sodium-potassium-chloride reabsorption.

Torsemide: The Longer-Acting Loop

Torsemide is the third major player in the loop diuretic family. Like its cousins, it blocks the Na+/K+/2Cl- transporter in the ascending Loop of Henle. The distinct advantage of torsemide is its bioavailability and duration of action. While furosemide’s absorption can be erratic (especially in patients with gut edema from heart failure), torsemide is absorbed much more reliably and stays in the system longer. This makes it an excellent option for chronic management of heart failure, potentially preventing re-hospitalizations better than furosemide in certain populations.

Hydrochlorothiazide: The Hypertension Staple

Moving past the loop, we arrive at the Distal Convoluted Tubule (DCT). Here we find the Thiazide diuretics, with Hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) being the most recognizable name. HCTZ inhibits the Na+/Cl- co-transporter. Because the DCT only reabsorbs about 5% to 10% of sodium, thiazides are less potent than loop diuretics regarding fluid removal.

However, this “gentle” action makes them perfect for long-term blood pressure control. They relax blood vessels over time and reduce fluid volume just enough to maintain healthy pressure without dehydrating the patient rapidly. For comprehensive guidelines on hypertension management using these agents, the American Heart Association offers extensive resources.

Chlorthalidone: The Thiazide-Like Powerhouse

Chlorthalidone is technically structurally different from thiazides, so it is often called “thiazide-like,” but it targets the same Na+/Cl- transporter in the DCT. In recent years, pharmacology experts have favored chlorthalidone over HCTZ for high blood pressure. Why? Because of its half-life.

Chlorthalidone lasts a very long time in the body (up to 24-72 hours), ensuring that blood pressure is controlled consistently through the night and into the next morning. HCTZ can wear off more quickly. This sustained action makes chlorthalidone highly effective for reducing cardiovascular events like strokes and heart attacks.

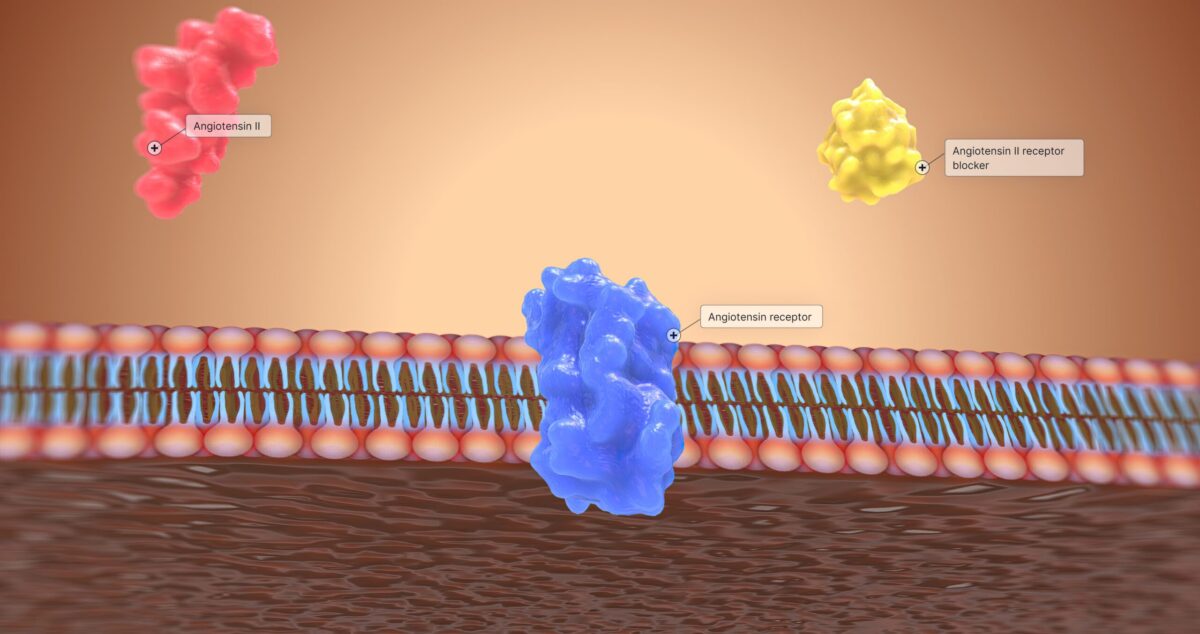

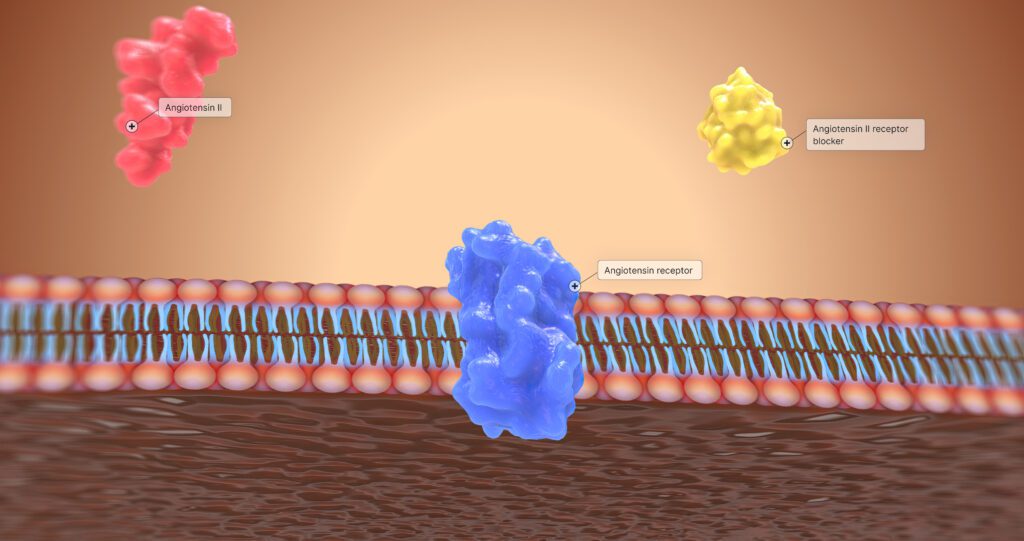

Spironolactone: The Aldosterone Antagonist

As we reach the end of the nephron—the Collecting Duct—we encounter the Potassium-Sparing diuretics. Most diuretics discussed so far cause the body to lose potassium, which can be dangerous for heart rhythm. Spironolactone solves this by working as an antagonist to aldosterone.

Aldosterone is a hormone that tells the kidney to save sodium and dump potassium. Spironolactone blocks this hormone’s receptor. The result? The kidney dumps sodium (and water) but holds onto potassium. It is widely used not just for diuresis, but for its hormonal effects in heart failure and liver cirrhosis.

Triamterene: The Direct ENaC Blocker

Triamterene is another potassium-sparing agent acting in the late distal tubule and collecting duct. Unlike spironolactone, it does not rely on hormones. Instead, it directly blocks the Epithelial Sodium Channel (ENaC). By plugging this channel, it prevents sodium reabsorption.

Because sodium isn’t reabsorbed, the electrical gradient that usually forces potassium out into the urine is disrupted. Consequently, potassium stays in the blood. Triamterene is rarely used alone; you will almost always see it combined with HCTZ (a combo pill) to counteract the potassium loss caused by the thiazide.

Amiloride: The Other ENaC Blocker

Amiloride functions almost identically to triamterene. It is a direct blocker of the Epithelial Sodium Channel (ENaC) in the collecting duct. It is a mild diuretic when used alone. Its primary utility in pharmacology is its ability to “spare” potassium.

Clinicians often add amiloride to a regimen involving loop or thiazide diuretics to maintain neutral potassium levels. It is also used in specific conditions like Liddle’s syndrome (a genetic disorder of hypertension) or lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus.

Canagliflozin: The SGLT2 Inhibitor

We now enter the modern era of diuretics with the SGLT2 inhibitors (“flozins”). Canagliflozin works in the Proximal Convoluted Tubule, the same area as acetazolamide, but with a totally different target. It inhibits the Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 (SGLT2).

Normally, the kidney reabsorbs 100% of filtered glucose. Canagliflozin blocks this, causing glucose to spill into the urine. Since glucose is an osmotic particle, it pulls water with it (osmotic diuresis). Originally designed for Type 2 Diabetes to lower blood sugar, it was found to have profound benefits for heart failure and kidney protection.

Dapagliflozin: Beyond Diabetes

Dapagliflozin shares the same mechanism as canagliflozin: blocking SGLT2 in the proximal tubule to promote glucose and water excretion. By reducing the volume of fluid in the blood and reducing sodium retention, it lowers the workload on the heart.

Dapagliflozin has become a superstar in treating heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, even in patients who do not have diabetes. It represents a shift in thinking—using a diuretic mechanism not just to “dry out” a patient, but to fundamentally alter the metabolism and hemodynamics of the kidney and heart.

Empagliflozin: Kidney and Heart Protection

Empagliflozin is the third major SGLT2 inhibitor. Like its siblings, it acts on the proximal tubule to block glucose reabsorption. The resulting diuresis helps lower blood pressure and improve weight management.

However, the fame of Empagliflozin comes from landmark studies showing it significantly reduces cardiovascular death and slows the progression of chronic kidney disease. While technically a “diuretic” because it increases urine output, it is now viewed as a foundational pillar of cardiorenal therapy.

Comparison of Diuretic Agents

Since we have covered a wide array of medications, here is a breakdown of how they compare regarding their site of action and primary mechanism.

| Drug Class | Specific Drugs | Nephron Target | Primary Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loop Diuretics | Furosemide, Bumetanide, Torsemide | Thick Ascending Limb (Loop of Henle) | Inhibits Na+/K+/2Cl- cotransporter. Highly potent fluid removal. |

| Thiazide / Thiazide-like | Hydrochlorothiazide, Chlorthalidone | Distal Convoluted Tubule (DCT) | Inhibits Na+/Cl- cotransporter. Mainstay for blood pressure. |

| Potassium-Sparing (Aldosterone Antagonists) | Spironolactone | Collecting Duct | Blocks Aldosterone receptors. Saves potassium, dumps sodium. |

| Potassium-Sparing (ENaC Blockers) | Triamterene, Amiloride | Collecting Duct | Directly blocks sodium channels. Mild diuresis, prevents hypokalemia. |

| Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors | Acetazolamide | Proximal Convoluted Tubule (PCT) | Inhibits Carbonic Anhydrase. Causes bicarbonate excretion (alkaline urine). |

| Osmotic Diuretics | Mannitol | PCT and Loop of Henle | Increases osmolarity of filtrate, holding water in the tubule. |

| SGLT2 Inhibitors | Canagliflozin, Dapagliflozin, Empagliflozin | Proximal Convoluted Tubule (PCT) | Blocks glucose reabsorption. Glucose pulls water out (Osmotic diuresis). |

Understanding these mechanisms allows healthcare providers to mix and match these drugs—a strategy called “sequential nephron blockade”—to overcome diuretic resistance and manage complex fluid disorders efficiently.